What is Art History Made of?

(Image of my hand holding an #arthistory hashtag in front of a man walking down a street in New York describing the work of Taryn Simon, 2013, Charlotte Frost)

Over the last few years I have been staging a practical and theoretical investigation of art historical media. I’ve been asking what are art history and criticism are made of? Of course, the simple answer is: words. When we interpret, contextualise and historicise artistic practice we, in the main, take something visual and turn that experience into one carried by words. But sometimes these words are spoken, some are printed in books and magazines and now, with the rise of digital technology and the internet, some of these words are digital. My concern is that not only do we, as art critics and historians overlook our own media in a bid to analyse and understand that of artists, but in doing so, we are ignoring what happens to art knowledge when it is rendered in different forms. So I decided I would have to render my own investigation in different forms.

I began to explore the nature of academic publishing with an open-access project called PhD2Published. A major forerunner in the now well-populated field of blogs offering advice on aspects of academic life, it was established not just as a resource but a tool. For example, by running the site themselves, participants can gain hands-on experience of writing across a range of social media, instantly increasing the forms their own work might take. With Gylphi, I set up Arts Future Book, the first academic book series dedicated to publishing works on the arts in experimental formats. Such projects are necessarily large and multi-faceted investigations into academic systems. They support each other and even spawn sub-projects that offer a wealth of useful data beyond my processing capacities alone. For example, the ever-expanding Academic Writing Month (a PhD2Published initiative) generates huge amounts of information on how academics write, the ways we describe our practice, and the fears we have about our own personal approaches. But these projects can feel overwhelming, and I wanted to strip art history down to one very simple element and explore the physicality of that element. I wanted to think about how art historians make art history.

(Image of my hand holding an #arthistory hashtag in front of a work by Sonia Falcone, Bolivia, Venice Biennale 2013, Charlotte Frost)

Taking all the research and learning from Arts Future Book and PhD2Published I wrote an article asking whether art history is too ‘bookish?’ My aim was to set up a discussion of the relation between ideas about art and essentially bookish elements. For example, does the juxtapositioning of image and text contribute anything to our belief that art can and should be written about and even, is there a way in which we read art which relates to the way we read books? I wrote ‘Is Art History Too Bookish?’ (rather than make video or do a dance), because I felt it was important to speak firstly to the traditional form of art history, but I didn’t want the article to appear in print. Instead, I set about exploring how it could be published accessibly, online and in a way that would allow for public comments. I wanted to create a space where peoples’ interjections or annotations were part of the work itself and where reading was perhaps a bit more active.

I also wanted to speak back to our unspoken assumptions that art historical writing doesn’t have (artistic, media-specific – even tendentious) forms of its own. That is, I wanted to draw attention to the physicality of art historical statements whether they are made in print or online. I wanted to look at art historical writing as an object.

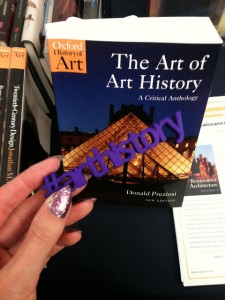

(Image of my hand holding an #arthistory hashtag in front of the book The Art of Art History: A Critical Anthology by Donald Preziosi on the Oxford University Press book stand at CAA 2013, Charlotte Frost)

I therefore worked with artist Rob Myers to create a kind of art object out of art historical text and one that might manifest the same sorts of questions about the form of art history as my article. In a way, I wanted an art object to parallel the article, but more than that, I wanted to make something that might help people think about the way we make art history with words. I believe that art historians already over-look the physical nature of printed art history, and that we are therefore completely oblivious to what digital art history is made of. And if the article itself compared print with online, so too should the artwork. We therefore took the classifacatory marker used on Twitter for all things art historical – #arthistory – and created a way for people to order a physical rendering of this hashtag. By visiting our http://hasharthistory.net website you can follow a link and order a hashtag to be 3D printed in a material of your choosing, and mailed to you for a cost-covering fee. Likewise, via the website you can find links to a range of ways in which the tag is being – for want of a better word – used. That is, we are encouraging people to order the tags and then use them in the real world the same you would use them in the digital world. If an image and or text is tagged ‘#arthistory’ on Twitter, why not take the 3D printed tag and apply it to something three-dimensional, and feed your results – usually an image of the tag next to an object – back into the digital realm by uploading it to Twitter, Flickr or Tumblr. I have embedded a Flickr gallery in the article, so that any images included in the #arthistory Flickr group automatically illustrate my article, while this project of creating – that is perhaps also occupying and subverting – a form of art historical writing can be taken in its entirety as an illustration of the discussion the article presents. For example: do we really know what our art historical statements are made of and how this impacts the way we use them and the type of knowledge they can carry?

(Image of 3D printed hashtags, 2013, David Frost)

I wrote and uploaded the article onto a WordPress website using the CommentPressCore plugin so people could comment on each paragraph individually. Meanwhile, Myers and I set up the network needed to explain the hashtags – where to get them and how to use them. This meant, as stated, making a Flickr gallery for users to upload images to but also that I had to get out there myself and start experimenting with the tag. In fact I first used a prototype of the tag out and about at dOCUMENTA 13 and it instantly transformed the way I record my art experiences. I would never have taken photographs at dOCUMENTA 13 had it not been for the fact I needed to start gathering pictures for the project as well as get used to juggling a camera phone and 3D print. I would usually rely on other people’s images and texts (in the form of catalogues and books), but the more I got used to tagging, the more I realised making visual and textual notes as I encountered artworks was valuable for my teaching and on-going research. I wasn’t just mapping my physical route through an exhibition, but also the journey my thoughts went on. And it was fun. I should mention now that of course the 3D printed hashtag is also supposed to be an enjoyable project. Yes I am trying to draw attention to the objecthood of art historical knowledge, but I also want to encourage people to play around with the concept of art history.

Eventually I had to set up a ScoopIt! site for all the elements of the project because there was so much overspill. For example, in this context, the Twitter stream for the hashtag ‘#arthistory’ is not just a public discussion channel but the site of an artistic intervention and though it’s embedded in the article and listed on the http://hasharthistory.net website, it’s a standalone element. Likewise I was soon interviewed by an art historian from Florence, Alexandra Korey, who co-runs an online marketplace for emerging forms of digital making (like 3D printing). Being asked to comment on the project in this context – as a form of critical making – was not an outcome I had expected but again it is an element of it and a way of demonstrating what happens when you work in a more networked environment than a book.

(Installation shot of ‘Dirty New Media’, 2013, Pete Ashton)

Most exciting of the unexpected outcomes, however, was the inclusion of several 3D printed hashtags in an exhibition at the Barber Institute of Fine Arts. I was approached by Antonio Roberts, curator of ‘Dirty New Media’, who asked if he could include the tags in the show. Here’s the description from the catalogue:

“These 3D printed models of the Twitter hashtag ‘#arthistory’ rendered here in plastic and in gold-plated stainless steel are a playful way to think about what art history might be in the age of social media and crowd-sourcing. The entire artwork comprises both the creation of the ability to render this piece of digital text in 3D form and its ownership/use by anyone. There is a dedicated website (http://hasharthistory.net) that explains the project and points to how the tags can be obtained. It also features links to places where you can see the hashtag in use and join in (i.e. tagging real world items as ‘art history’), these include a Flickr gallery, a Tumblr blog and of course the #arthistory Twitter stream. The project is also a three dimensional and/or practice-based rendering of an argument made by Charlotte Frost in an online art history article entitled: ‘Is Art History Too Bookish?’ In this article – which is deliberately offered online, rather than in print – Frost asks after the extent to which the format of printed books have contributed to the way we think about art. In this sense, the tags ponder the physical nature of textual objects and the future of art discourse. The work is also closely related to Myers’ series of ‘Sharable Readymades’ which is the creation of 3D printable models of iconic works of art.”

Perhaps more important than their inclusion in an art exhibition (and therefore their categorisation not as art historical text but as art objects themselves) was that they were displayed next to iconic works of art including ‘Maria Marow Gideon and her Brother, William’ (1786-1788) by Sir Joshua Reynolds . In many respects this was the consummate gesture: art historical text being appreciated for its object-hood while retaining its function as classificatory marker; the art of taxonomy as art.

(Image of my hand holding an #arthistory hashtag in front of a wall text at the Venice Biennale, 2013, Charlotte Frost)

Likewise, the digital form of my article had me make a mail artwork out of gaining peer-reviewers. As I published the article online and outside of a respected journal I was relying on email, Facebook and Twitter to publicise it’s existence. Two high-profile digital scholars got stuck in and commented/reviewed the article fairly quickly and I am extremely grateful to Jussi Parikka and David M. Berry. But how do you get an open access/digital article on digital art histories publicly peer reviewed by non-Tweeting academics? You send out 3D printed versions of it to three-dimensional art historians of course. I wrote the http://hasharthistory.net URL on some paper tags, tied them to the hashtags mailed them to James Elkins, Amelia Jones and Griselda Pollock. Elkins relished the mystery reviewing the article and writing: ‘Thanks so much for the surprise, and the puzzle!’

In gathering images of the hashtag I have also begun to think about the tremendous variety of contexts within which we make judgements about historical validity and what counts as art. Without initially intending to, I have started physically tag the wonders of the world. And perhaps ironically, my efforts to explore the digital life of art history have increased my exploration of the physical world. The tags have been to dOCUMENTA 13 and the 2013 Venice Biennale opening, but so too have they visited the Taj Mahal:

(Image of my hand holding an #arthistory hashtag at the Taj Mahal image also known as ‘The Money Shot’, 2013, Charlotte Frost)

and Stone Henge:

(Image of Image of my hand holding an #arthistory hashtag at Stone Henge, image also know as ‘Hashtagged Henge’, 2013 Charlotte Frost)

I set out to draw attention to the physical specificities of the forms art historical knowledge takes. From books to hashtags, I collaborated on the 3D printed hashtag to make an object out of art historical scholarship. In a sense, I was working in a similar vein to Lori Waxman whose project ’60 wrd/min art critic’ stages the act of doing art criticism within a gallery context and therefore forces us to think about criticism as both a practice and an creative work itself. And in fact, one of the main things to come out of my ‘bookish/#hashtag’ project is that I’ve begun to consider exactly what it is my own art historical work entails. I am already working on a study of the way I work on a daily basis. Yet I have also started to develop new ways of working.

In 2012 I was invited to give the Keynote at Duke University’s ‘Critical Ink’ conference on writing. I began by talking about how I’d learned to blog by knitting and to knit by blogging, such were the cross-overs in openly shared methodology and three-dimensional thinking. And now I am gradually developing a practice where I make to understand (art) writing and write to understand (art) making. As an art historian I was trained to study other people’s creative experiments. Not only that, but I had been encouraged to extract the essence of an artwork and distil it as writing alone. I was taught to close read and then close write, but never paint, sculpt or computer game about an artwork. Art historical writing becomes a sort of one-way transmediation which appears to assumes the ultimate form of knowledge is writing – an assumption which seriously undermines its object of study. This method has greatly contributed to the invisibility of art history’s own physicality. I’d argue that some ideas about art are made of writing while others are made of making, and digital technologies offer us valuable insight into these different critical modes. With this project I have not only begun to explore the specific nature of different forms of art knowledge and shone a spotlight on my own practice, but I have also begun to build a more multi-modal and experimental practice for art history scholars and those working in the digital humanities. I have started to model what I hope will become a valuable creative and practice-based approach to investigating the contextualisation of art.

#arthistory is such a great idea – I think you’ve really got something here with the entire project. The way you’ve documented everything and created your own remixed images with the 3D printed text overlay is a really smart way of dealing with copyright – I may use your work to teach my students about copyright when I ask them to do digital projects.